MY LATE great friend Tom Christensen amassed a collection of over 1500 VHS videotapes before he passed away, sadly right before the influx of DVD. They covered an entire wall in his den, from top to bottom. Tom could quote dialogue from every movie he owned too, and more besides that. He was amazing in that way.

Tom also had an affection for 1950s science-fiction and horror films. So do I, for the most part, though the older I get the harder it is for me to sit through one without getting either disappointed, or bored, or both (with exceptions of course). In fact, I find it hard to believe that anyone could still watch a random SF film from that era without feeling anything but derision.

Unlike Tom, I was far more judicious when it came to collecting movies on tape. I only bought about a hundred or so during VCR's heyday, starting with Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Road Warrior and Star Wars. I replaced them all eventually with discs, but I did hang onto a few of the boxes because I thought they were cool. Most weren't though. In hindsight, I should have hung on to them all. They are now considered by some to be a retro commodity, especially if they still have their tapes.

From the 1950's I have only these four boxes remaining:

IT CAME FROM OUTER SPACE (1953) was based on an original story treatment written by Ray Bradbury. In it (no pun intended), a spaceship crashes in the Arizona desert and its benign alien crew are forced to disguise themselves as humans in order to get the materials they need to repair their ship in secret.

Feature Film and Television writer Harry Essex (1910-1997) altered Bradbury's dialogue and then took credit for the entire screenplay, which was so typical of what went on in Hollywood back then and probably still does. Essex was even awarded a 1953 Retro Hugo Award in 2004 for Best Dramatic Short Form Presentation. How Bradbury felt about that is not known to me but Gauntlet Press chronicled all of Bradbury's involvement in a 2004 book titled the same as the film (pictured just below). It included, along with an abundance of essays, letters, photos, marketing posters and advertisements, Bradbury's two story outlines (actually there are four); one containing malicious aliens, the other with benign aliens. Said Ray: "The studio picked the right concept, and I stayed on."

The film was originally seen in theaters in 3-D, but the VHS was strictly standard 2-D. That's since been amended, and now you can enjoy the film in either format on DVD and BD.

SUSAN Osborne, one of my favorite former library colleagues, discovered the joy of 1950s science-fiction movies late in life. She was particularly enamored with FORBIDDEN PLANET (1956) and its leading man, Leslie Nielsen. To her he was a hoot! Me, I couldn't stand the guy! Still, because Forbidden Planet was loosely based on Shakespeare's Tempest, and the film's sets, special effects and robot were, at the time, beyond amazing, it has always held a special place in my mind, if not my heart.

What most people don't know is that prior to the film's theatrical release a novelization appeared in hardback in February, 1956, published by Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, (pictured just below), and then later in paperback from both Bantam (March, 1956, pictured further below), and Paperback Library (October, 1967, also pictured below along with a few foreign editions). It was written by Philip MacDonald, a highly respected mystery novelist, writing under the pseudonym W. J. Stuart. MacDonald explored the film's many themes, sexual and otherwise, in mostly greater detail using multiple first person accounts, and while his written work doesn't always jibe with the film's dialogue and scenes, the novel still gets my recommendation, pulpish though it may be (best of luck though, in finding an inexpensive copy).

'FORBIDDEN PLANET is based on the MGM Cinemascope and color production of the same name, starring Walter Pidgeon, Anne Francis and Leslie Nielsen. Screenplay written by Cyril Hume, from the story by Irving Block and Allen Adler. Directed by Fred Wilcox and produced by Nicholas Nayfack.'

'A space-adventure story with highly imaginative backgrounds, constant action and an unusual psychological twist, this is science fiction of the first order, written by a master hand. At the opening of this fantastic tale of the future and earth spaceship is launched to seek the survivors of an expedition some twenty years before to Altair 4 (one of the earth-type planets). The chief characters of the new expedition are Commander Adams, Lt. Farman and Dr. Ostrow--men trained in a world dedicated to science and peace, men with original purpose and integrity. When they arrive on Altair 4 they find the sole survivor is Dr. Morbius, but that he now has a mysterious and strangely beautiful young daughter, Altaira. She is extraordinarily gifted. Morbius warns the earth-visitors that they must leave at once, that there is a malignant influence on Altair 4 that has already destroyed everyone else in the former expedition. The visitors do not heed his warnings, as they are cared for by an amazing robot, whose huge, mechanical but seemingly gentle ministrations brood over them. Terrifying adventures follow. An unseen presence, a deadly menace, haunts them. Although warned not to do so, they dare to explore in a forgotten and destroyed generation of spacemen, the Krells. The awakening of Altaira to the earthman's ideal of love, and final escape climax this colorful and macabre romance.'

.ForbiddenPlanet.BantamA1443.a.jpeg)

This movie-tie-in paperback edition was published by Bantam in March, 1956. The cover art was not credited and was likely derived from one or more of the studio's lobby poster concepts.

"They were experienced space explorers. They'd sweated in the jungles of Venus and tasted the dust of dead planets. But nothing prepared them for Altair 4. It was a paradise--sure. A topsy-turvy Garden of Eden--with green moonlight, golden grass... and the astonishing girl, Altaira. But there was horror behind the beauty. There was non-human intelligence at work--And then there was the sudden, shrieking, agonizing death..."

'Soon after landing on Altair 4, Commander Adams and the crew of Spaceship C-57-D are confronted by Dr. Morbius, a strange scientist who plots to become Master of the Universe. Morbius warns the earthlings to leave at once--or be destroyed by his Invisible Force. Commander Adams and his Spacemen choose to stay in a desperate attempt to stop Morbius. Despite terrifying attacks on their spaceship, they race against time in an unbelievable search for the key that would unlock the mad doctor's secret. Their fantastic battle against incredible dangers makes FORBIDDEN PLANET a unique, unforgettable science-fiction shocker.'

Corgi's paperback edition was published in the United Kingdom in 1956. Englishman John Richards produced the cover art. Richards (1915-1964?) worked mostly for Corgi during the 1950s and early '60s, producing covers for some of the biggest names in SFF, adventure, espionage and mystery. But it was his masterful jacket art on the hardback novelization of Creature From the Black Lagoon (Dragon, 1954) that I think he will be remembered for the most. For many cinephiles, myself included, that particular edition has become the Holy Grail of SF movie-into-book collectibles.

'ALTAIR 4 was in sight! They had traveled billions of light years through dark, treacherous space--their mission to rescue the lost crew of the spaceship Bellerophon. And now the radio crackled with life--someone was scanning them! Someone on the planet was alive! They crowded around the radio as a thin but steady voice said: "This is Morbius speaking." It was Edward Morbius, captain of the lost expedition. The cruiser C-57-D responded immediately, "We've come to rescue you. We will land within minutes." Morbius' thin metallic voice now bit out sharply--"There's no need to land... no need for assistance... no need to land... It might, in fact, be disastrous!'

This is the forbidden planet--Altair 4. And this is the story of the Earthmen who risked everything to conquer its secrets.'

French publisher Hachette published this softcover edition also in 1957. Their cover art was not credited, nor is it signed.

* * * * *

A LARGE meteorite crashes to earth and shatters into hundreds of black fragments. Each one is capable of reproducing and expanding again and again to enormous heights when exposed to rain water. The fragments, or silicon-based crystals, also have the ability to petrify humans. An ecological disaster is iminent unless the scientists can come up with an effective deterrent.

Okay. Got it.

What we have now is "The Killer Rock Movie." Sounds stoned, I know, but in fact 1957s THE MONOLITH MONSTERS is one of the most serious and sober films of the Fifties era, and patently intelligent with its use of pseudo-petrology-science. The special effects are amazing too. To this day no one really knows how Clifford Stine created them (Stine also created the meteor crash in the opening of It Came From Outer Space, borrowed for opening use here in this film as well). The Monolith Monsters is one of those rare B movies that despite its formulaic script is amazingly original and fun to watch, and doesn't ridicule itself.

(Note: There are no books that have made or adapted from this film.)

* * * * *

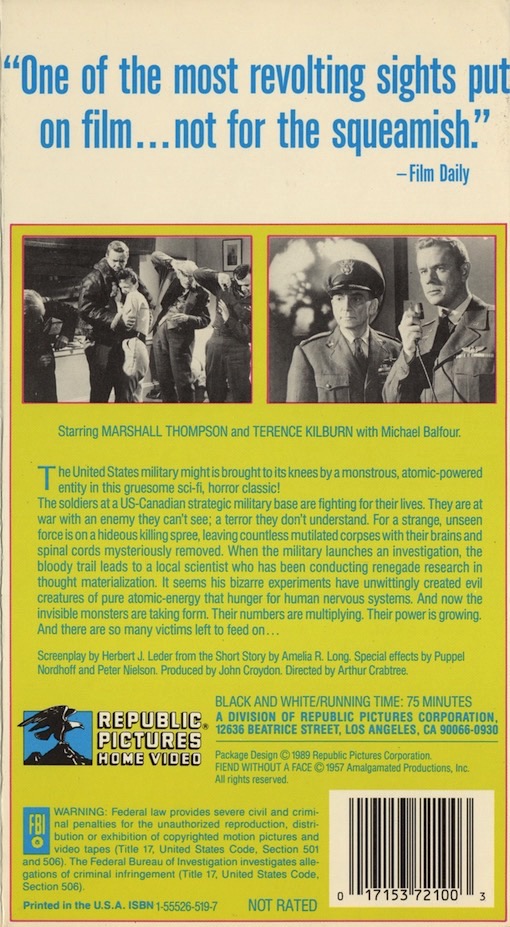

FIEND WITHOUT A FACE (1958) is without question the best "Killer Brain Movie" ever made. But that's not saying much because this film doesn't have a whole lot of gray cell competition. Only eight other movies have been made that have actual brains wreaking havoc on people. Though, that is eight more than our "Killer Rock Movie" has going against it. Three of those films-- The Lady and the Monster (1944), Donovan's Brain (1953), and The Brain (1962)--are loosely based on Curt Siodmak's 1942 science fiction novel Donovan's Brain. The other five are based on original treatments: The Brain from Planet Arous (1957), Mindkiller (1987), Blood Diner (1987), The Brain (1988), and Brain Damage (1988).

Without question though, Fiend Without A Face has a superior frontal lobe than all of those movies put together, or at least its finale does. Sadly, its first half is mind-numbingly dull, and has in place about as plodding an investigative procedural as has ever been filmed or directed. If you don't find yourself slumped in your chair with your eyes lolling in the back of your head then you are probably on illegal stimulants (which I would never endorse). But when the insidious "brain fiends" finally do materialize in the second half you will sit up like you just got zapped by radioactivity, and be wowed at the most outrageous science fiction finale ever made in the Fifties.

"Sluuurp"!

(Note: There are no books that have made or adapted from this film.)

* * * * *

PS: Fiend Without A Face made me think about our good blogging pal, Dan, at Dead Man's Brain, who has been inactive since October, 2019. I hope everything is okay with him and that his little gray cells start singing again like Poirot's.

[© June 2021, Jeffersen]

.FarrarStraus&Cudahy.asb..jpg)

.ForbiddenPlanet.PaperbackLibrary.JackGaughan.art.a.jpeg)

.ForbiddenPlanet.Corgi.JohnRichards.art.a.png)

.ForbiddenPlanet.Mondadori.CarloJacono.p3.illus.jpg)

.FobiddenPlanet.Hachette.Paris.a.jpeg)

.ForbiddenPlanet.Mondadori.KarelThole.art.a.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment