"They were ripping up the Rovaniemi airport, as they were almost every airport in FINLAND that summer, into big piles of rock and sandy soil. It was all part of some grand rebuilding design ready for the day when the had enough tourist traffic to justify putting the jets onto the internal air routes. In the meantime, it was just turning perfectly good airports into sandpits."

"You're a weird one, Cary. What are you really wanting out of life?"

I sat down beside her. She turned quite naturally so that her head was on my shoulder. I ran my hand gently through her hair. The cabin was quiet and close around us.

"I want to find nickel," I said.

She looked up at me with a wry smile. "Not gold or diamonds?"

"Just nickel, I hear that some people make money just by finding oil."

"It's happened." She moved her cheek gently against my hand. " And what'll you do when you find it?"

"Get myself a new plane, or two. Maybe start a real company."

She turned further and her breasts crushed against me and her hair was in my eyes, and I wanted her. Not hungrily or frantically, but very strongly and certainly. From loneliness, perhaps, but not the loneliness of the forest or of Lapland itself. And maybe because she carried her own loneliness with her, too.

"Maybe I'll buy you a new plane after all," she said sleepily. "I could make money at it. I think you'd be a good risk."

I lifted her head and kissed her and her body reached against me, strong and soft at the same time. And there was no world outside the cabin.

Then she pulled firmly away and sat back on her heels; looking at me with her grey eyes wide and not at all sleepy now.

"Just because I'm getting divorced," she said gravely, "doesn't mean I can be got just by grabbing."

"I know: I'd get sued for a million dollars."

"And don't get tough with me, Cary. I can't take much more."

"Yes, you can." I reached and ran a knuckle down the sharp line of her jaw. She shivered suddenly and then caught herself. I said: "You've got enough guts and singlemindedness for the whole United States Marines. If you hadn't, money would have loused you up a lot more than any one man could."

"You pay the prettiest compliments." But her eyes relaxed. "You're a bit of a hard bastard yourself; that's why I think you'd be a good investment. But of course, you're only here to nine o'clock." She smiled lazily at me.

"I thought that big business knows no hours."

"You're learning, Cary. You're learning."

She leaned slowly forward and I reached for her. And there was no hunger; just a gentle strength moving from loneliness to a great calm.

Lyall proved in his fledgling effort that he was pretty good at implementing description. Here's a prime example:

Up above us, on our right, the hump and the village of little white houses looked very steep. A narrow-stepped path wound up and vanished behind the first cluster of the houses. Ahead of us, another path led through the wiry clumps of grass behind the sand. I had expected to find it marshy: it wasn't. There should have been a stream, but there wasn't that either. Probably the village had tapped it off, further back.

I took the lead. The grass reached for about another hundred and fifty yards and was pretty flat and level until, as the valley sides began to close in, it rose up towards the cypresses.

If there was a plane in among those trees I still couldn't see it. I didn't notice a thing until I was within twenty yards of the first tree. Then, suddenly it was there; an outline among the columns of the trees. It was one of the weirdest sights I ever saw.

It was a Dakota, lying flat on its belly with its wings along the ground. It was pointed away from us, up the gentle slope, and turned slightly left, just as it had come to rest ten years before. In that time, the trees had grown up close around it, so that you could never see it from the air save by flying directly overhead, and then only by the faint outline defined by the trees themselves.

Aeroplanes are my business, and Dakotas are my specialty---but not this one. When I stepped in among the trees the sounds of the sea behind me and the light and warmth of the sun were cut off as if a door had closed behind me. I felt very much alone. The trees were so thick that almost no sun would ever reach the ground in here, but the shadows had the same lucid quality as the light outside. And it was very still. There is nothing as still as a grove of thin straight trees, and no trees as still as these.

In ten years the Dakota had taken on a green-grey shadowy colour that made it belong there. It didn't look as if it had crashed. It had come there, and it had meant to come there, and when it had come the trees grew up around it as part of it, and it had turned into something natural. It looked a thousand years old. It made me think of other groves where men were half goats and that this aeroplane belonged more to them than to me. It looked like a shrine. I began to get a prickly feeling in my hair.

Yup, Lyall could write. Even in the infancy of his career he could write, and this is as good a debut as you'll find by anyone.

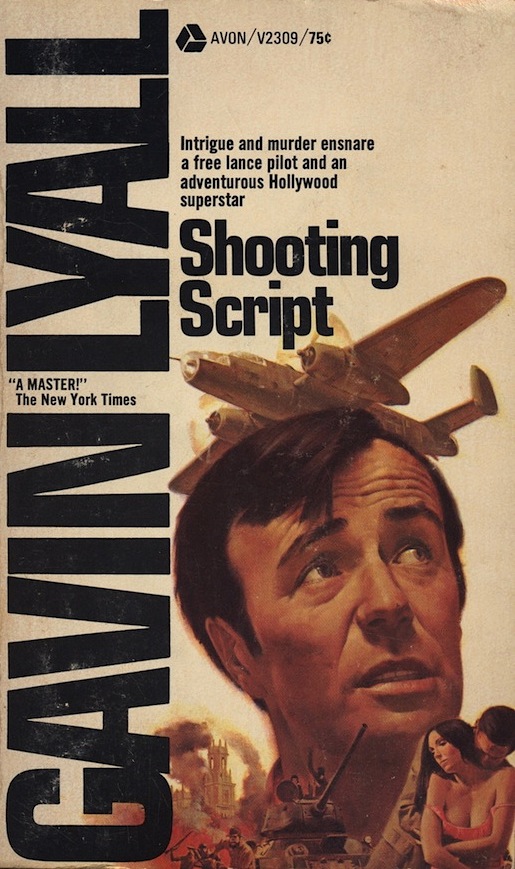

Below is an interesting action scene from Shooting Script where the Dove is being menaced by a Vampire. Inside the Dove's cockpit are Carr and Walt Whitmore, an American director and prospective client of Carr's. Whitmore was actually modeled after actor John Wayne, whom Lyall befriended during an actual film shoot:

Whitmore twisted around, watching the Vampire over his shoulder. "You figure he's going to shoot?"

"I figure on keeping out of his sights." Was that all I figured?

We were below 1,500 feet now and still going down in wide spirals. But the Vampire had learned something, he'd positioned himself only about 500 feet higher this time and---as far as I could judge---he'd slowed down a lot. He circled in a gentle turn outside our spiral, waiting his moment.

Keeping an eye on the Vampire, I put my right hand down on the flaps lever. "Get your hand on this," I told Whitmore. "When I say 'Flaps' I want it all the way down. But not before. Don't practice." I felt his big paw push mine aside.

He said calmly: "Got it."

I waited until the sun was where it wouldn't blind the Vampire or me, turned extra steeply for a few seconds, then straightened out as if I'd spotted where I wanted to go and was heading there direct.

Come on, you bastard: try and bite me.

He bit. He flipped over and came down in the classic "curve of pursuit," the long curling dive to end up sitting on my tail.

I turned into and under him again---but now he was expecting that. He was moving slow enough to follow me. He tightened his diving curve, holding me easily, swinging smoothly into firing range.

I leveled the Dove and pulled back the throttles. The Vampire slid behind my left shoulder, almost dead behind us. I yelled: "Flaps down!"

The lever clicked in the silence. Then it was as I'd stamped on the brakes: the Dove collided with a soft pillow of air and bounced soggily upwards, into the Vampire's path.

Suddenly he was on top of us.

He reared like a startled horse, jerking into a wildly tight turn. His wings blurred with mist, condensing in the shattered airflow, the flicked level as he stalled out. He shuddered past a few yards to the left and I caught a glimpse of a helmeted hunched figure in the cockpit, fighting controls that weren't controlling anything any more. His nose began to swing inexorably downwards.

A Vampire can lose over 2,000 feet in a gentle stall. This one had only 1,200 feet to lose---and he was as totally stalled as I've seen an aeroplane. There was nothing to do now but watch him die.

To bale out of a Vampire 5 you dump the cockpit canopy, roll on your back and drop out---if you're still in control.

I put the Dove's nose down, pushed up the throttles: we were close to stalling ourselves. Below, the cockpit canopy flashed off the Vampire, so perhaps he tried at the last second to jump. Then he was a burst of flame and a swelling cloud of smoke on the harsh green countryside. From inside the dove you couldn't even hear the bang.

The Scavengers by Allan Nixon (Avon, May, 1969).

'Buck Shannon came to the Pacific to find Patricia or to get her out of his system. But Patricia's husband--Buck's brother Mike, who might be alive or dead--turns up very much alive and up to his neck in trouble. In a volcano of violence a deadly game is played out under the constant threat of a howling, murderous typhoon that threatens to engulf all the players--even before they kill each other!'

The Monument by James Kubeck (Avon, June, 1969).

'The IONA MAY was a marked ship. Full to the gunwales with explosive cargo, it had no way to run and no place to hide. Enemy bombers were taking their time, letting the men of the IONA MAY sweat. Then Captain Elliott killed himself and left Harris the command he'd always wanted....'

The Luck of the Lonely Sea by Patrick O'Hara (Avon, August, 1969).

'Cursed by a seemingly jinxed vessel, Karl Schepke steers the GERTRUD LUTH across the tempestuous China Sea and up the treacherous Yangtze, deep into Red China. There he encounters a new kind of danger: two political stowaways who create a lashing and lethal storm of their own and write a violent, suspenseful climax to THE LUCK OF THE SEA'

The Sea Chase by Andrew Geer (Avon, December, 1969).

'The ERGENSTRASSE was a dying ship. But its imperious, fanatic Captain Erhlich was something else again. Pitted agains him and his crew of murderous men are two unlikely, but formidable adversaries: beautiful, tormented Elsa Schweppe, the single woman aboard, and Napier, a lone, young British lieutenant. Defiantly the ERGENSTRASSE plunges ahead--and a cruel war within a war is on in this furious, thrill-filled and shrewdly psychological epic of the sea.'

|

| CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE |

'Johnny Kinsman was an ordinary young man--until he joined the RAF. He found a purpose in life in the airborne hell over Germany. Then his unwilling love for his best friend's girl gave him reason not only to fight well, but also to survive...

And remember my mention of designer Milton Charles? Well, it turns out that Kastel was the stepback cover artist for one of Charles's most successful creations: Pocket Book's 1976 paperback edition of Judy Blume's Forever. Yes, it's more of that reoccurring likelihood of mine.

With the exception of his early 1960's covers, I can now say that I'm able to recognize most of Kastel's later cover illustrations with just a sustained glance. Knowledge, and nerdish concentration, is indeed, empowering.

[© 2016. Revised in August, 2018, Jeffersen]